Today is the feast day of Martin of Tours, a 4th-century Roman soldier whose most legendary biographical anecdote tells of his halving his military cloak with his sword in a generous act to warm a freezing man encountered on the road.

After leaving the Roman forces and converting, Martin dedicated himself to the early Church, establishing some of the oldest monasteries in Gaul and later becoming Bishop of Tours. Martin gained astonishing popularly after his death and was highly venerated in the Middle Ages. In the many centuries since his life and works were documented by a contemporary, Martin’s patronage and feast day observances have vastly expanded from France to much of Europe and indeed all of the Christian world.

Interpretations of Martin’s attributes, the cloak and the sword, are somewhat antithetical. A soldier firstly, Martin is revered as patron of soldiers and is affiliated with many military groups and army corps. Yet we understand from his hagiography that Martin’s hatred of violence accounts for his renunciation of military life. As such, he is also patron of peace and peace movements, and moreover his feast day is both Armistice Day and Veterans Day. In many ways then, Martin is linked to both the laying down of arms and the very vehicle through which violence is committed (soldiering). And despite his concurrent associations with generosity and protection, Martin’s fervor for the newly legitimized Christian faith rendered him a rather zealous destroyer of Roman pagan sites of worship. While perhaps from a distance of 15+ centuries we can overlook such acts, common as they were among the church-building, evangelizing early Christians of Martin’s Day, still these biographical tidbits are not easy to reconcile with his reputed anti-violent character.

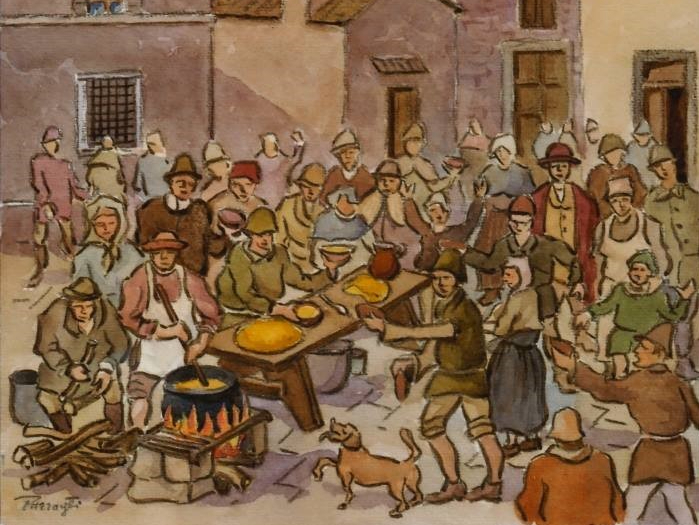

Since the Middle Ages, Saint Martin’s Day has been associated with the kind of exuberant festivities that frequently precede a fasting period (later, Advent). Falling at the end the harvest, specifically a point in the European agrarian cycle that sees annual livestock sales and slaughter (hence Martinmas beef and goose), Martin’s Day celebrations also happen just as young wines intended for immediate drinking arrive. In fact, in Italy la festa di San Martino coincides more or less with the arrival of vino novello (the less fussy cousin of Beaujolais nouveau), a link cemented in the popular Italian saying a San Martino ogni mosto diventa vino, meaning something like “on Saint Martin’s day, all must becomes wine” (the must has done fermenting). Note the drunken, spirited revelry depicted above in Bruegel’s The Wine of Saint Martin’s Day for an idea (perhaps exaggerated) of Martin festivities among land laborers enjoying the harvest’s new wine.

Throughout all of Europe, in both religious and secular manifestations, Saint Martin’s Day continues to represent a liminal period of seasonal, physical, and liturgical transitions, marked by the kind of feasting and merry-making that so often accompanies rituals of change or passage. Interestingly, although Martin’s Day is not as widely celebrated in Italy as in other European countries, Venetians celebrate Martinmas (which in other parts of Europe is also known as as “Old Halloween”) with customs similar to guising—children romp about town, banging pots and pans as they go from door to door, singing for candies and cakes much like Halloween trick-or-treaters. Praises are sung for those who give out treats, while curses and jibes are launched at the miserly. Watch some Venetian children doing just that in this San Martino “video postcard” from 2013. Other treats distributed to children on this day include San Martino cookies made in the shape of Martin on horseback or Martin holding his sword.