An Italian polentata is a polenta festival similar to countless other food-centered events in Italy broadly referred to as sagre, and in this case an event that highlights polenta’s associations with Ash Wednesday observances and customs.

Long associated with the Lenten period on account of its “lean” quality—being a simple, frugal dish using no meat and relatively little fat (often none at all)—polenta is served on this day to mark the end of the “fat” celebrations that culminate on martedì grasso and the onset of customs such as fasting, penance, and atonement.

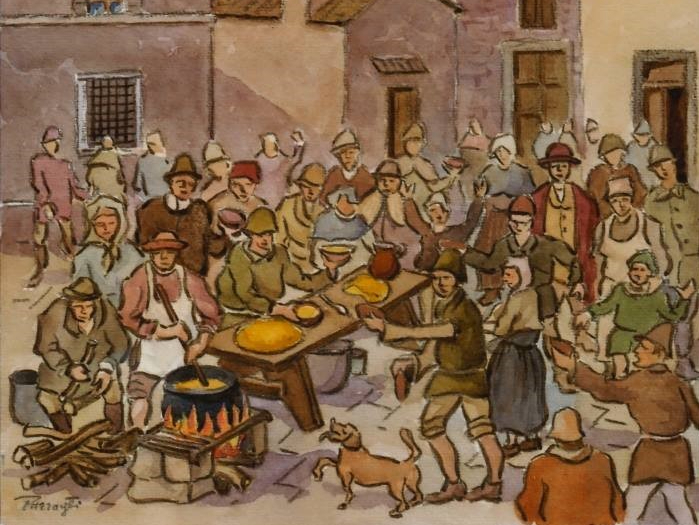

In Borgo San Lorenzo in northeast Tuscany, locals have been organizing a polentata on Ash Wednesday every year since 1800. It’s one of the longest-running folk events in the Mugello region, with a celebrated backstory that’s hard not to get a little enthusiastic about. In 1799, following the French invasion of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, a battle to push out French troops took place in the streets of Borgo (much of the Mugello and Casentino areas were influenced at that time by the resistance movement Viva Maria, centered in Arezzo, where resistance fighters took back their city after Napoleon invaded). After a furious battle in the streets around the Borgo San Lorenzo castle ended, and the dead had been buried, local housewives and peasant women set about cooking huge potfuls of polenta to feed the stricken survivors.

The following year the polentata took place on Ash Wednesday, becoming known as la polentata delle ceneri (cenere = ash), and has been held every year since in the town’s Piazza Garibaldi. According to Aldo Giovannini, an area journalist and historical image archivist who has published numerous books on the Mugello, the polentata was kept a humble affair, free of the concerns of social class—a testament to la libertà.

pictured: detail of Enrico Pazzagli’s “Watercolor Depicting One of the First Polentate, Early 1800s”