December has become, for many, a time to reject the saccharine and materialistic version of Christmas and embrace instead the magical stillness of Midwinter’s long, dark nights.

For me, it is also a time to wonder at the fascinating cast of folkloristic figures who make their appearance this month—starting on Saint Nicholas’s Day (and eve) through Twelfth Night and the Feast of the Epiphany.

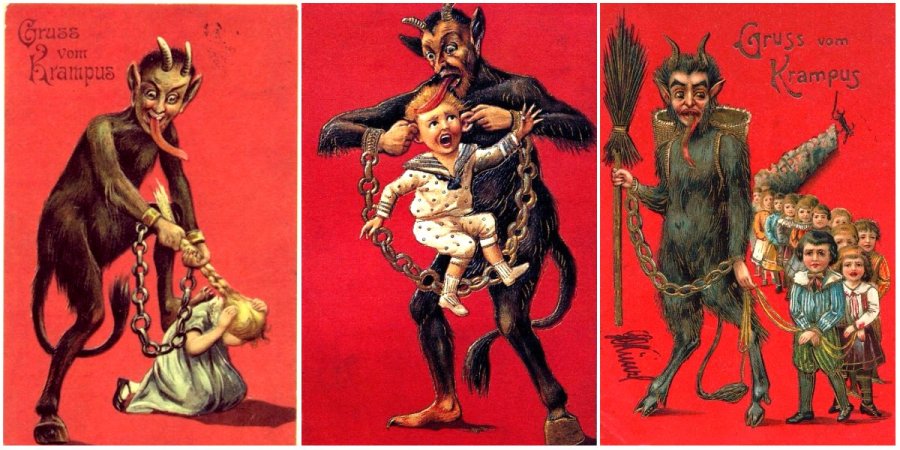

Among these characters, Krampus has lately taken center-stage as the most popular of Saint Nicholas’s sidekicks. In the past decade, in fact, Krampus has climbed from his relatively unknown status (outside his native Germanic/Nordic realms) to one of global Christmastime superstar, with books, articles, social media campaigns and even movies dedicated to him, while his annual parades, the Krampuslauf, grow evermore crowded, elaborate, and visually documented each year.

His primary function is counterpart to Saint Nicholas: Nicholas rewards, while Krampus punishes. His typical punishments come in the form of whipping and shoving children into his sack, to be carried off to his lair. Or maybe to hell. It depends on the version of the lore, really, and the naughtiness of the particular child. He can sometimes be placated with a offering of schnapps.

Many people question the appropriateness of Krampus, in particular his seemingly glorified acts of terrorizing children into being “good”. A counter-response I’ve frequently encountered asks if such a practice is any worse than bribing children into not being “naughty,” or exacting any type of specific behavior through the promise of excessive, superficial rewards (such as overpriced plastic crap and sugary foods).

I think it’s important to see Krampus and his fearsome ilk as much more than winter “monsters”. He is a link, a sort of figurative bridge between the pre-Christian pagan beliefs and practices observed by peoples in Europe’s Northern and Alpine regions and the later figures who came to represent the Christianized version of Midwinter (Saint Nicholas, Santa Claus). Moreover, if we are paying attention, Krampus reminds us that our ancestors spent this time of year in connection with the natural world and in deep contemplation and acknowledgement of darkness and death. Celebrations took place, of course—think of the ancient Roman festival Saturnalia, for instance, from which we’ve inherited fascinating Midwinter concepts and practices such as misrule, disguise, inverted social roles and norms, etc—yet, broadly speaking, this time of year has turned into one of forced cheer and joy only relatively recently.

Krampus’s surge in popularity may also represent a growing need to express our distaste with what Christmas has become, a way to purge oneself of antithetical ideas and feelings not permitted, even taboo, during this be merry or else season. In that sense, Krampus and his acts might be considered cathartic. Personally, I find his revival promising: a sign of increased interest in these fascinating forms of ancient deep winter observance and festivity.

image courtesy of Davide Bon