The Alps span several geopolitical borders and encompass significant cultural and linguistic diversity, and yet it is a region, when considered as a geographical entity rather than as a serious of nations, united by its folk customs.

Rooted in pre-Christian, nature-worshipping Alpine religions, many local legends, calendar customs, and artisanal crafts in Italy’s Trentino-Alto Adige/South Tyrol continue to reflect the deep connections with the natural landscape that characterize Alpine folklore and folkways. Grounding them all is a ritualistic acknowledgement of the extreme seasonal shifts, isolation, and solitude inherent to mountain life.

Alpine Beastmen. South Tyrolean festivities that mark significant cyclical transitions—such as the winter and summer solstices, the end of the harvest, or the arrival of spring—feature a host of folkloristic figures who congregate in spectacular public events. These include the Perchtenlauf, followers of the pagan Alpine goddess Perchta who are collectively known as Perchten. The Perchten wear frightful animal costumes and bang on massive drums to drive out winter darkness as they follow their leader, a Hex who symbolically “sweeps up” the previous year’s evil to be tossed into the fire.

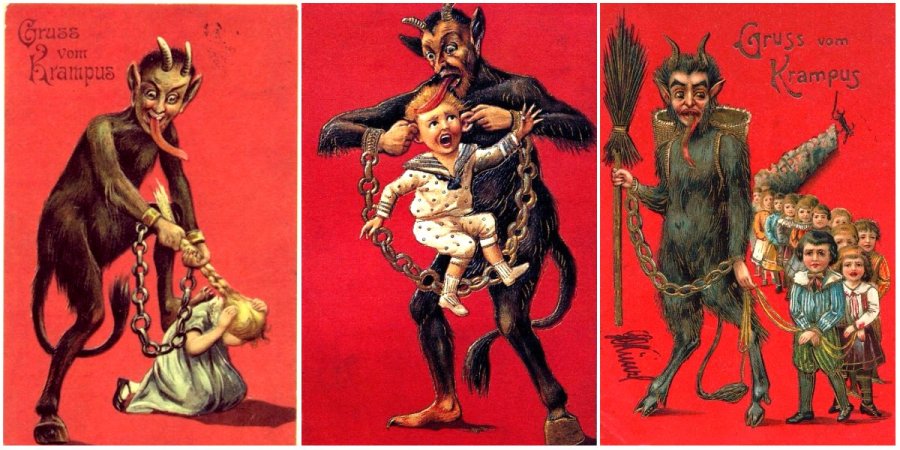

A similar figure is Krampus, another anthropomorphized beastman who inhabits the wintry Alpine and northern European realms. Every year, on the eve of Saint Nicholas Day, Krampuslauf parades take place throughout Trentino-Alto Adige, in towns like Pergine (near Trento) and Dobbiaco (east of Bolzano), with Krampus teasing and terrifying onlookers as part of the larger Saint Nicholas festivities.

Other customs in this region include the Klöckeln, when costumed figures knock on farmhouse doors in villages like Varna and Scalares in the Val Sarentino on the first three Thursdays of Advent—the Christian liturgical season leading up to the arrival of Christ. Similar to winter mumming, the ritual involves great secrecy among the participants, whose peculiar white masks, long mossy beards, and floppy red noses entirely disguise their identities. According to tradition, sweets and wine must be offered to the Klöckeln, who then conclude the visit by etching a crucifix on or near the threshold, such as on the doorfront or in surrounding snow.

Wood Carving. South Tyrol’s long tradition of wood carving can be admired in places like Val Gardena in the Dolomites, where local artisans have been carving wooden toys, figurines, and large, elaborate nativity scenes for centuries. Wood carving is also the foundational craft employed to create Krampus’s strikingly grotesque and beastly appearance, typically made from local pine. The masks are then further embellished with ram or goat horns, furs, and faux skins, before being painted to frightening effects. The Maranatha Nativity Museum in Luttago (in the province of Bolzano) houses a collection of these handcrafted masks, with an atelier showcasing their evolution from blocks of wood into depictions of the devilish face we associate with Krampus.

Summer Bonfires. Lighting bonfires—falò in Italian—to mark the summer solstice is an ancient and common practice throughout Europe, derived from pre Christian sun worship rituals that in Italy have merged over centuries with Saint John the Baptist observances in late June. The practice continues today, with the month of June in South Tyrol seeing its mountain slopes and high peaks light up in a dramatic display of flames, creating a wondrous spectacle that spans the dark-of-night landscape for miles.

In a specific derivation of the midsummer falò tradition, South Tyroleans commemorate the successful Tryolean defeat of Napoleonic forces in June of 1796 with the lighting of Herz-Jesu Feuer, or Sacred Heart of Jesus fires. These fires, which are lit on the third Sunday after Pentecost—coinciding with the summer solstice period—recall the Tyrolean troops’ pledge to the Sacred Heart as they organized their defense against the imminent French invasion. The act of burning immense heart shapes and crosses in June has come to symbolize resistance, Tyrolean unity, and divine protection.

pictured: Klöckeln in Sarntal Valley; photo @ sudtirol.com

nb: a version of this piece first appeared in Italy Magazine’s Bellissimo, Winter 2023 Edition, Trentino-Alto Adige. Subscribe here!