Every Ash Wednesday, the town of Gradoli in Lazio hosts a peculiarly named event: the pranzo del purgatorio, begun in the 1300s by the Fratellanza del Purgatorio, one of countless confraternities in Italy dating to the medieval period.

The event unfolds throughout the town in various phases. Prior to the lunch, the confraternity members march through Gradoli soliciting “fat” donations like prosciutto and other cured meats, livestock, or even cash. Sellable items are then auctioned in the piazza, traditionally to fund Holy Mass for souls in purgatory and the Ash Wednesday lunch for the poor. The meal, intentionally magro (lean) to mark the start of the Lenten season, consists of fish from nearby Lake Bolsena and a special variety of stewed white beans, flavored simply with herbs and olive oil. These small, soft-skinned, no-soak beans have been associated with Gradoli’s purgatory brothers so long that they’ve come to be known simply as fagioli del purgatorio—purgatory beans.

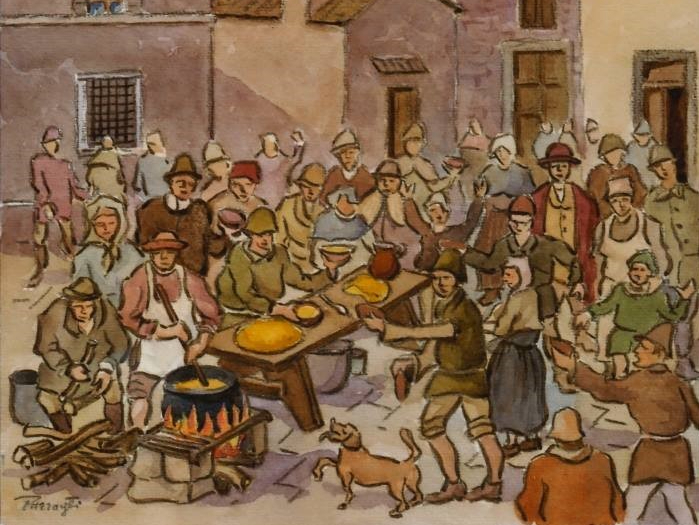

In recent years, Gradoli’s pranzo del purgatorio has transformed into a massively popular sagra that hosts hundreds if not thousands of participants. In La Cucina delle Tuscia: Storie e Ricette, Italo Arieti notes that while the menu of fish and beans remains unchanged today, the event has apparently lost its former overt associations with penance and abstention and gained an atmosphere of festive abundance (reflected by portion sizes, for instance). Arieti also tells us that those who join the lunch are no longer obliged to continuously chant Viva le anime nel purgatorio! for the souls in purgatory.