It’s nearly impossible to overstate the significance of Giuseppe, foster father of Christ and patron saint of fathers, who functions as a symbolic paternal figure for Italians and whose feast day is, not by coincidence, la festa del papà.

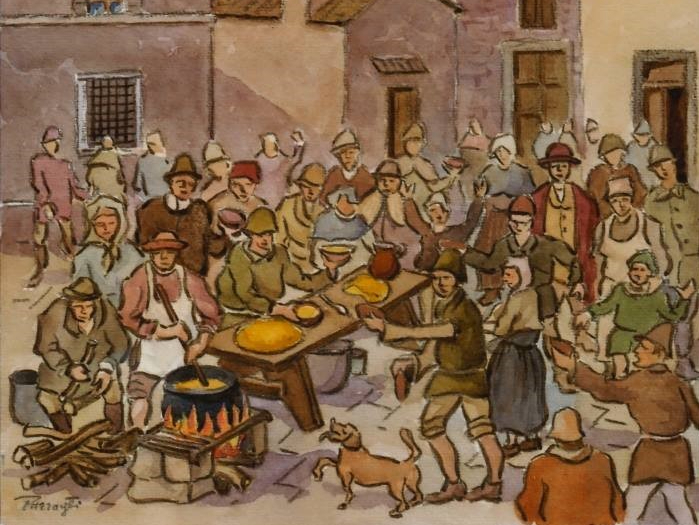

Marked by abundance and giving, Saint Joseph’s Day is a categorically food-focused celebration of spring’s bounty. In countless communities throughout southern Italy and Sicily, the days leading up to March 19 see an ambitious and communal food-making endeavor, resulting in banquets so lavish and plentiful they seem to mock the very idea of hunger, if not vanquish it outright for the remainder of the year. No matter how many hungry guests gather round one’s table on San Giuseppe, there must always be leftovers to give to neighbors or homeless people.

At the center of the feast is the Saint Joseph’s altar or table, upon which this mountain of food will be arranged. Nothing is placed on the table by chance; every item embodies some emblematic association or auspicious end. Bread takes center stage, as the most perfect expression of man’s toils transformed into sustenance, and recalling as well the ancient Roman grain festivals once observed during the winter-spring transitional period. Sweets, particularly fried and cream-filled pastries, mean a temporary reprieve from fasting and abstinence during Lent. Flowers, asparagus, wild fennel, and fava beans laid around the table speak to springtime’s imminent return, while lemons, oranges, and wine represent the fruit of the preceding season’s labors. Fish-based dishes symbolize Christ, and meat is usually absent from the table.

The countless fascinating food rituals surrounding this holiday derive from both ancient pagan and early Christian customs. In more recent centuries, thanks to Italian immigration, San Giuseppe festivities have taken root in other parts of the world—namely America, where Italian-American communities celebrate the saint with large, potluck-like events. Here are some of the Italian foods and lore associated with this significant feast day.

Fava beans. Several spring vegetables are linked to Joseph’s feast day, yet none so strongly as the fava bean, or broad bean. According to legend, a group of drought-stricken Sicilian farmers faced starvation until the saint intervened on their behalf, bringing about a miraculous crop of fava beans. This otherwise lowly legume has since come to represent Joseph’s generosity and benevolence, and in honor of him fava beans will be placed around the table or cooked in various dishes. Moreover, the fava bean has earned a lucky charm status among Catholics, some of whom will attend mass with a fava bean in their pocket on the day.

Maccù di San Giuseppe. Perhaps no dish embodies the transitional nature of this holiday so well as the stew known as maccù di San Giuseppe. As the move from one season to the next is often characterized by purging and cleaning rituals, the customary emptying of the pantry around the equinox is said to account for this many-ingredient concoction. All the items of last season’s harvest—dried beans, peas, lentils, chestnuts—are tossed into the pot along with fresh greens, wild fennel and fava beans (of course). In making maccù di San Giuseppe, Italians at once honor the saint and ready the pantry for the spring-summer bounty to come.

Focaccia di San Giuseppe. In Puglia, a special kind of focaccia is made in honor of Giuseppe, one whose unique combination of ingredients reflects the local taste preference for things agrodolce, or sweet and sour. Anchovy, young white onions, and raisins are added to a focaccia dough with a high olive oil content, which is then rolled into a spiral shape and baked. The bread likely owes its affiliation with the saint to the type of onions used, harvested this time of year before the onion bulb is fully formed and the stalk is very tender and flavorful.

pictured: a Saint Joseph’s altar in Salemi, Sicily featuring a stunning array of homemade votive breads